One day while wandering the halls of 20 Jay, looking for prospective Dumbo Direct members, I had the good fortune of running into Sandra Levinson, Director of the Center for Cuban Studies. She invited me in to explore their art space on the 3rd floor, one of Dumbo’s hidden treasures and I had the honor of hearing her amazing life transforming story about her first trip to Cuba. When Dumbo Direct became a reality, I knew I had to share Sandra’s story with my neighbors. Read about Sandra’s vintage voyage set in 1969, the summer of love, along with two other vacation tales as told by Mary Perillo of 911 Environmental Action and Raphael Alvarez, a filmmaker with Fly On The Wall Productions. Wishing all of our members happy travels. If you have a story to share, please let us know.

Travel Can Change Your Life

By Sandra Levinson

Executive Director of the Center for Cuban Studies and the Cuban Art Space

I hadn’t traveled a lot in my life, mostly on the train between Mason City, Iowa, where I was raised, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, where I was born. Always by train since my dad worked for the Rock Island Railroad and our train rides were free. I graduated from the University of Iowa, received a Fulbright grant to study abroad and finally left Iowa for good. Sailing on the grand ship, Queen Elizabeth, I couldn’t help but think, this is the life. How do I build a love for travel into an ordinary work life?

For a year I studied at the University of Manchester, lived with three terrific English flat-mates, and thumbed my way to London each weekend to visit other Fulbright friends. From the UK, I traveled to California for the first time, and entered graduate school at Stanford. After that, I got my first teaching job at CCNY. New York at last. I had definitely left Iowa behind. But my real travel was yet to come.

While teaching, I started working as the New York Editor of Ramparts Magazine, a ground-breaking radical journal edited by Warren Hinckle which, in the few years of its existence, managed to put the rest of journalism to shame: we were the first to reveal that the CIA was working its way through U.S. campuses; that we were dropping Napalm on Vietnamese civilians, that dirty work was being done by our Special Forces there, and to reveal in detail U.S. involvement in the assassination of Che Guevara. I was also co-host on a local PBS/Channel 13 show called “Free Time,” and had interviewed Daniel Ellsberg, Germaine Greer and other fascinating public intellectuals and writers.

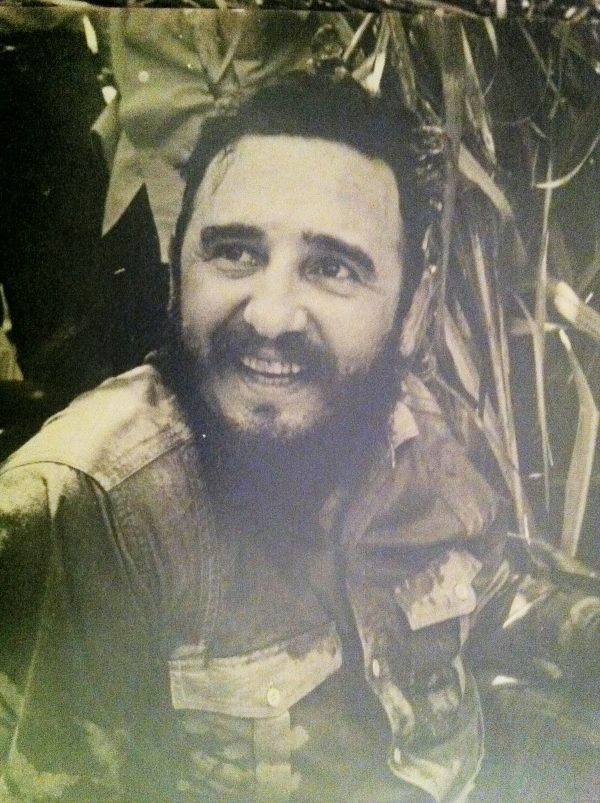

As a journalist and political activist, I received an invitation to travel to Cuba in 1969 (the only legal way then to travel to Cuba. Fidel Castro was about to announce an economic push to harvest 10 million tons of sugar cane in the 1969-70 season and journalists the world over were invited. Only three accepted from the U.S.: Saul Landau, a filmmaker and journalist I’d met at Stanford, ABC’s Peter Jennings, newly arrived from his native Canada, and me. I was also invited to give a few lectures on the history of McCarthyism in the U.S. and to get to know something about the Cuban Revolution at the same time. I planned to stay for two weeks.

The only way to travel to Cuba then was through a third country. The Cuban invitation suggested Mexico. I found out that Saul and other California friends were also going to Havana, so we all met in Mexico City to get our visas at the Cuban Embassy and take a (free) Cubana flight to Havana.

The plane to Havana was filled with enthusiastic young U.S. leftists, all invited by the Cuban government. In moments of reflection, I thought about what I was about to see and learn and had to admit that, although I considered myself a socialist and this would be my first visit to a real socialist country, I didn’t know if I would like it. I’d grown up in a country that hated communists and made almost no distinction between a communist and a socialist. As the only Jew in my class from kindergarten through high school, I’d often joked that being a Jew and a Democrat in Mason City, Iowa was like being a Communist somewhere else.

And, after all, I wasn’t immune to the anti-communism of the U.S. I didn’t like the Soviet Union either and yet “communist” was what most people heard when I talked about my socialist ideals. I knew that Cuba and the Soviets were tight now that the U.S. embargo effectively blockaded us from knowing Cuba and vice versa. So this is what I thought: I’ll probably really admire what the Cubans are doing in trying to build a revolutionary society—but I wouldn’t want to live there. My imaginings about socialism were a kind of sociopolitical grey, with everyone thinking and acting alike in metaphorical lockstep. I wasn’t a lock-step person. In-between teaching and journalism, I marched, demonstrated, and protested, sowing the seeds of the 60s generation.

I arrived in Havana on a historic day (for the U.S.), July 4th. I was a lucky traveler because Saul had already dug his journalistic heels into Cuba, he’d even made a terrific documentary about Fidel, up close and very personal. So I knew that hanging around Saul was the way to get to know this “first free territory of the Americas,” as the Cubans had dubbed themselves after defeating the U.S.-backed Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961.

Within days I had met and come to admire some of Cuba’s best writers, artists and filmmakers, all friends of Saul. I had already abandoned the idea of never wanting to live there. Peter Jennings, as a Canadian, found it impossible to understand why the U.S. had broken relations, invaded and embargoed Cuba. He kept asking Saul and me, “Why Cuba?” It was a question that could only be answered in the context of our own peculiar anti-communism that had jailed, exiled and sidelined a generation of leftist artists and activists. What I came to love about the Cubans was their openness.

So, here I was at last, my first socialist country. The Cubans were smart, educated, knowledgeable and reeling from the constant attacks from the U.S., a country they’d known growing up in a complicated relationship: colonizer, mentor, partner, landlord, boss, friend, etc. But never ENEMY. The Cuban government reached out to us, journalists and political friends, in large part to try and understand why our government had chosen Cuba as its primary target.

We were all staying in the Havana Libre hotel which until 1959 was the last new hotel built in Havana. The Habana Hilton opened in March, 1958, with five days of partying and Conrad Hilton himself there to launch the tallest and largest hotel in Latin America. U.S. socialites, actors and journalists partied around the clock. Within months this gigantic investment had tanked and was renamed Free Havana! And here we were, free guests in this free hotel. It was overwhelming.

But this first trip to the Caribbean, my first trip to socialism, was not really about free meals and free hotels. It was all about talk. There was nothing the Cubans wouldn’t talk about, long conversations late into the night. I found a country where Cubans worked hard all day and played and talked hard all night. They were learning about socialism and the revolution too. Ten years into their revolution, people my own age were still trying to adjust to the revolutionary reality. They’d grown up under the Batista dictatorship and those that preceded Batista; their ideas of freedom and independence were the same as those taught to me in grade school, ideals of the French Revolution. They admired the U.S. and our own fight for independence. They thought our countries should be friends or, at the very least, not enemies.

Okay, you’re thinking, another starry-eyed leftist blinded by the light. I don’t think so, and I didn’t then. Not long after my first trip, Time magazine described the Cuban Revolution as socialism with salsa, recognizing Cuba’s unique twist on what the U.S. saw as just another communist outpost of the Soviet Union. What I saw was a young country in a fight for a free and independent Cuba: abandoned by its longtime partner, now protected by a country with which it had no history and little in common. Within days I knew from these long conversations that Cuba would be for me a special experience, one that would inform my teaching and my take on life in extraordinary ways.

I was right. On the fifth day of this first visit, the invited journalists, together with Cuban reporters and foreign journalists resident in Cuba, were taken to another part of Cuba for the opening of the 10 million ton sugar harvest. Peter, Saul and I only knew that we would hear Fidel speak the next day. All of us journalists were in a small hotel outside of the northeast city of Holguin. We were awakened at 3 am for a breakfast of fruit, ham and cheese sandwiches and café con leche and then piled into buses. We drove to Puerto Padre, site of a major sugar mill, arriving about 6 a.m., to wait for President Castro, whom everyone called Fidel. Me too, even though I’d never met the man. We were all excited.

Most of the visiting journalists were from Mexico and other Latin American countries; the foreign journalists living in Havana were from everywhere in Asia, Africa, Europe. Why hadn’t any U.S. journalists except Peter accepted the Cuban government’s invitation when they were all desperate to learn about Cuba? I asked Jennings. “They can’t accept a free trip from the Cuban government, their editors won’t let them. It could compromise what they write.” “Not if they’re true journalists,” I replied. “Why did your ABC bosses let you come?” “Because I’m Canadian,” he pointed out.” We can travel to Cuba anytime we want. We have diplomatic relations and no embargo.” There was one U.S. journalist living in Cuba, Lionel Martin, who had written for The Guardian newspaper in the U.S.

A huge crowd awaited Fidel. We non-Spanish speaking journalists were given earphones for translation and were seated on a platform above the crowd, alongside where Fidel would speak. A Cuban journalist pointed out Che Guevara’s first wife, the Peruvian economist Hilda Gadea. It all seemed unreal. At 8 am Fidel arrived to loud applause and shouts from the crowd. He began to speak in a soft and direct voice about Cuba’s economic problems and hopes for the future. He was spellbinding and very different from his portrayal in the U.S. press. He spoke for two hours and after the speech, which outlined a year of hard work, sacrifice and cane-cutting to harvest more sugar than ever before in Cuba’s history, all of us went back on our bus, thinking that we were returning to Havana.

I promptly fell sound asleep, as did many others. Suddenly, the bus shook and stopped. I woke up to find that we were in a sugar cane field and we were all invited to come out of the bus. There in the middle of the field was Fidel, surrounded by perhaps 20 journalists; wearing a straw hat and a sweat soaked shirt, it seemed clear that he’d been cutting cane with the workers behind him who were still cutting away. Everyone was hot and sweaty. Saul, Peter and I joined the other reporters and we sat there for at least an hour while people threw questions at Fidel, all answered thoughtfully—I managed to squeeze myself into the front so that I was a foot away from Fidel. With my little Olympus half-frame I took more than 70 photos of Fidel that day. My Spanish was so minimal that I didn’t understand most of what was being said.

Suddenly from the back, a Japanese journalist living in Havana, shouted out, “Comandante, we would like to show our solidarity by cutting cane with you today!” Great idea, Fidel responded, and asked that machetes be passed out to the journalists. Obviously, Saul, Peter and I had no intention of cutting cane. We stood at the back while the others collected their cutting tools and prepared to attack the cane. Saul and Peter were deep in conversation and I was watching with wonder as all of the others picked up their machetes and started cutting.

“Suddenly from the back, a Japanese journalist living in Havana, shouted out, “Comandante, we would like to show our solidarity by cutting cane with you today!” Great idea, Fidel responded, and asked that machetes be passed out to the journalists. ”

Suddenly there was a hand on my arm. It belonged to Fidel. “And you?” he asked. I tried, in my broken Spanish, to explain that there was no way I was prepared to cut sugar cane. I didn’t know how and besides, I had a very weak wrist as a result of a bout with polio as a child. “Come, come,” Cuba’s leader coaxed. “I’ll teach you. You’ll do fine.” And without waiting for an answer, he put the machete in my right hand, stood behind me and guided my machete-wielding arm in the proper movement to cut the cane, as though I was being taught to swing a golf club. I was terrified and at the same time, unbelieving. The president of Cuba is trying to teach me to cut sugar cane???

After about 10 minutes, Fidel said he thought I had the hang of it, “Okay, let’s cut cane!” I could see that Saul and Peter were doubled over with laughter. I felt like an idiot but also very proud that I was about to cut sugar cane with Fidel Castro. He was a serious teacher and he had taught me well in those ten minutes. He stuck by me and I wasn’t bad at swinging the machete, cutting down the cane and then picking it up and tossing it onto a faraway pile. Most of the other journalists were in front of us, a few behind.

The work is hard as hell. I can see why Fidel later said that there’s nothing revolutionary about cutting cane, it’s backbreaking work which should be done by the U.S. canecutting machines Cuba is not allowed to import. We had been cutting together for about 20 minutes when a missile went into my neck and I collapsed in pain into the canefield. Lionel Martin, cutting behind me, had accidentally lobbed his cut cane not onto the pile of cane, but into my neck. I felt like I’d just been hit by a truck. I started crying but then I saw Fidel’s boots coming toward me to pick me up and all I could think was that I should stop crying, “Revolutionaries don’t cry!” But I felt awful.

Fidel and his physician aide, Chomy (vice-rector of the University of Havana), and my guide, Carlos, all examined my back for obvious injury. Fidel said he’d drive me to Lenin Hospital in Holguin for xrays, which he did. Thus began a challenging physical saga for me, carrying me through two spinal surgeries in Havana and years of physical therapy. But at that point I survived just fine, and instead of the two weeks I’d planned, I abandoned my Woodstock trip and remained in Cuba for six weeks, traveling the entire country and beginning the journey that would shape my life for the next 50 years. For the first time, I began learning what it really means to try and make a revolution. It didn’t scare me away, it made me more determined than ever to try and change my own country, and to help this small country which I saw as successfully defying the ungenerous country we were becoming.

Sandra Levinson is the Executive Director of the Center for Cuban Studies and the Cuban Art Space, resident in Dumbo since January 2018 at 20 Jay Street, #301. The Center is open to the public Monday-Saturday, 12-6, and by appointment. The Art Space exhibits contemporary Cuban art year round, presents authors of books on Cuba, shows Cuban films and has a gift shop filled with crafts from Cuba.

The White Cows of Pushcar

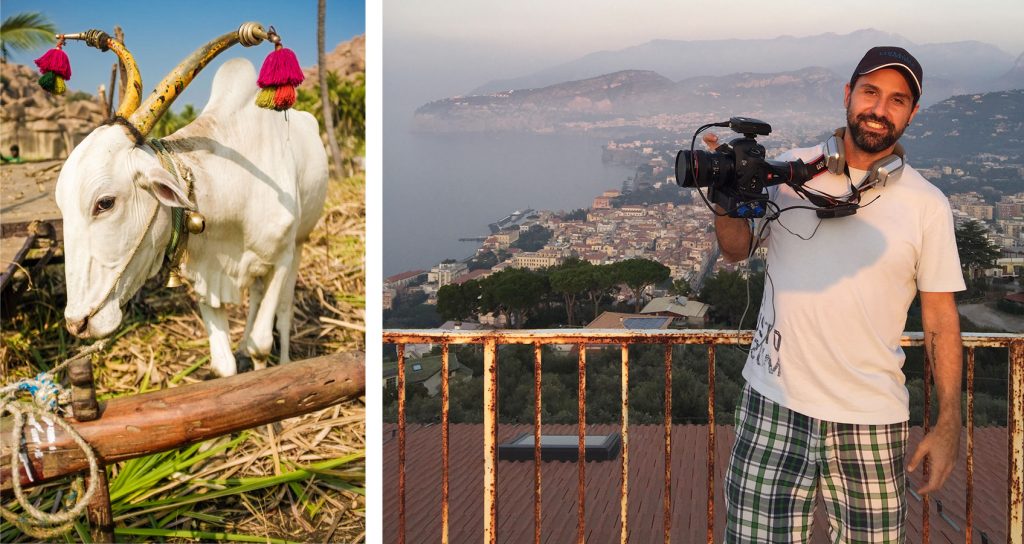

By Raphael Alvarez of FLY ON THE WALL Productions

I had just come off a long work assignment in India and along with others in the crew we decided to take a week off to relax. We followed a glowing recommendation to visit a town called Pushcar. Our drive went smoothly until the road came to an abrupt end. A man on the side of the road informed us that a motorcycle would come and drive us to our hotel, which he described as “ A great hotel, the best in the town.” We had hired a driver so we did not need to abandon our car however we had expensive film equipment as well as many heavy pieces of luggage. After several exhausting trips on the bike we finally arrived at our destination to find that there were no locks on our hotel doors. Brazilians always carry locks with their luggage. We pulled one off one of our suitcases and installed it on the door.

For some reason there was rice all over the room, as well as the bathroom, showers, sinks, etc. The floors were covered. We also noticed that there was no toilet paper. When we asked for a roll the concierge looked at us in complete shock. When we pleaded to buy a roll from the hotel, our request was abruptly denied. After a long tiresome trip we had to use the facilities badly. It was an emergency situation. We ran 8 blocks back and forth to buy a pack at a local store and made it back just in the nick of time.

Famished from the long trip, we were pleasantly surprised to notice that there was pizza being prepared in the hotel. When we ordered a pie my friend was told that it was not for human consumption. It was exclusively reserved for the hotel mascot, the white cow.

At this point we decided to relax and take a walk around the town. My friend took out his camera and started photographing a small herd of holsteins. Apparently the cows were either camera shy or did not like Brazilians and started chasing us all around the village. No matter what street we turned down they were at the other end staring at us and ready to charge. We finally made it safely back to our room.

The next day we went to the only Hindu temple in Pushcar that allowed meat eaters to enter. We took off our shoes as required. As we exited, I encountered a serious problem, my shoes were stolen. They were nowhere to be found. I would have walked back to the hotel barefoot but the streets were covered in cow manure and there was no hot water in our room. My friend ran back to fetch my only other pair of shoes…

When we both returned to the hotel, the management felt very badly about all of our misfortunes and promised a big bonus as an apology for all of the inconveniences that we had endured. We were expecting a nice meal or even a discount on our bill however the bonus as it turned out was the honor of meeting the white cow. She was a beauty and preferred her pizza with or without anchovies.

Matera, Italy

By Mary Perillo of 911 Environmental Action

In 1956 my grandmother, Brunetta Maria Venezio, was my babysitter in Bushwick, Brooklyn. I was one or two years old at the time and spent hours in her kitchen playing with dough and being fed amazing foods that I never knew the names of. This year I visited her hometown, Matera, the village where she learned to cook and wash the family’s clothes in a river down a steep ravine.

Named as this year’s European Capital of Culture, Matera, Italy has a beautiful medieval town and corso on top of the ravine. However, my grandmother came from the rougher geographic cliffside region of Matera known as the “Sassi”. The “Sassi “was also referred to as the as the shame of Italy. Rife with illness, including cholera, infant mortality at that time was at a shocking rate of 50%. Living among the cave dwellings in the “Sassi” was a very difficult existence and once she left for America, it was a place my grandmother never wanted to see again.

In the 1950’s the Italian government removed all the residents of the “Sassi” and it remained empty until the late 1980’s when the rock churches began to be used for art projects. I was there in1989 to film a concert of a NY jazz trio. We worked below but stayed and ate above. This city has been inhabited for more than 900 years and fortuitously it was given the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. Thankfully, it will be preserved.

This June I went back with my partner and spent a week exploring the streets and stairs of the “Sassi” where now there are B+Bs, small hotels and amazing restaurants. Not only was the “cucina povera” delicious and healthy (thick greens beans, grains and olive oil and smokey sweet dried crunchy peppers) but the smells and tastes coming out of the kitchens brought me back to 1956 Bushwick. For me, it was both travel and time travel.

I carried photos of my grandparents through the trip. The pictures opened many doors for my partner and I as did my grandma’s name, Brunetta Maria Venezio who was named after the patron saint of the town.